Filling a Food Locker: Class Discussion Turns Into 282 Pounds of Impact

In Dr. Ashley Davis’s Human Development Through the Lifespan (PSYC 211) course, a conversation about hunger became a tangible, campus-centered service project that filled shelves at the Carroll Food Locker and gave her students a compelling lesson in how communities can care for one another.

The spark came during a chapter on health, when the class showed keen interest in the realities of food deserts and food insecurity. As Dr. Davis put it, “It’s sometimes very difficult to predict like what the students will be into. But they were super talkative.” The discussion ranged from easy access to fast food versus the distances many rural residents must travel to a grocery store, an angle students found especially eye-opening and relatable.

And then Dr. Davis did something simple, yet powerful. She made a proposal to her class: for every A grade earned on their midterm, she would donate an item to the Carroll Food Locker. The idea translated engagement into action, without putting the burden on students who might already be struggling with food insecurity themselves.

I think projects like this brought my class closer. The conversations we have are even better now because they’re even more comfortable talking amongst each other in class.

Breaking Down Barriers

Dr. Davis treated the Carroll Food Locker project as course-aligned learning. She reminded students it’s a resource, not a stigma. Her message was direct and compassionate: “I said it’s nothing to be ashamed of. This is something that we have at the College and if you need it, it’s here for you.”

That framing mattered. Dr. Davis said she wanted “to break down a barrier.” In a course that emphasizes the “interconnectedness of our society,” the Food Locker offered a concrete place to see how systems, policy, and daily life collide—right there on campus.

What began as a pledge tied to midterm performance quickly grew. “I thought, let me see how big I can make this,” Dr. Davis recalled. She then reached out to her family and friends, explaining the class discussion and the role campus resources play for students. The response was immediate and generous: “They went above and beyond. I raised $965.00.”

With that money, she shopped strategically, guided by the people who know the Food Locker best. “I asked my student who volunteered at the Food Locker to tell me what items were the greatest need, and she said hygiene items,” Dr. Davis shared. She then went to Costco to buy food along with such high-need essentials as toothpaste, body wash, deodorant, and other personal care items that don’t reliably come through traditional food donation streams.

A Hands-On Helping Activity

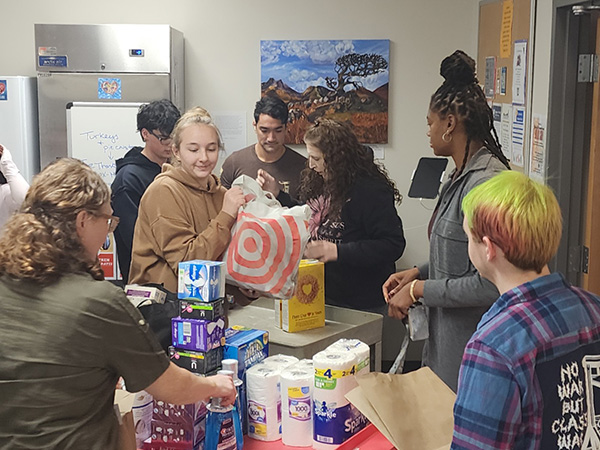

The project didn’t culminate with a simple drop-off. Dr. Davis and her class went together to restock the Food Locker, turning donation into direct participation. “I was so touched to see how they just jumped right in,” she said. The students, working as a team, started assigning roles, with some sorting the items, some weighing them, and some stocking the shelves.

The total weight of all the food and hygiene items came to an impressive 282 pounds. “We had enough stuff that we were able to pack the closet,” Dr. Davis said.

But what surprised Dr. Davis most was how little she had to manage the moment. “If you had talked with me before we went down there, I would have probably said, ‘Oh, I’m going to have to make sure they’re organized’ and tell them, ‘Hey guys, come on, focus.’ But I didn’t have to do any of that.” The class built its own workflow and, in the process, built something else too: a stronger sense of community. Dr. Davis saw the impact ripple beyond the shelves. “I think projects like this brought my class closer. The conversations we have are even better now because they’re even more comfortable talking amongst each other in class.”

Lessons Learned (and Lived)

What started off as a class discussion quickly became something students could see, interact with, and take ownership of, turning course concepts into something real—with real impact.

- Food insecurity isn’t theoretical, and it isn’t only “somewhere else”

Students didn’t just analyze national data; they connected it to lived experience. Dr. Davis noted that during their discussion, “Some of them mentioned that they themselves or people in their family had utilized food banks or support services in the past.” That honesty shifted the topic from abstract to human, and helped create empathy without pity. - Reducing stigma is part of serving

A Food Locker can exist, but it only helps if people feel comfortable using it. Dr. Davis acknowledged that “especially on a college campus where adolescents are naturally more insecure than adults are, students are more worried about what other people are thinking.” Her goal then was to make support services feel “accessible and not scary.” - Needs include hygiene—and dignity matters

Students learned that food drives often overlook other items people truly need. Dr. Davis emphasized the “cost differential” between food and personal care products and challenged the common habit of donating what’s unwanted. “When you’re donating things to people, are you donating things that you don’t want or are you donating something that you would also want to receive?” Students even joked about the quality of some of the items she’d purchased—“Oh, Professor, you got bougie stuff!”—but the message resonated: dignity isn’t a luxury. - Action can be local, manageable, and meaningful

One of the most important lessons wasn’t about scale; it was about doability. “I think one of the strengths of this for my class was that we didn’t have to leave Carroll,” Dr. Davis reflected. “I did something manageable with what we already had.” It’s a model of service-learning that doesn’t require coordinating bus trips or complicated planning—just unselfish purpose and follow-through.

Demetrius Quillen, a student in Dr. Davis’s PSYC 211 class, reflected on the experience’s broader meaning: “The Carroll Food Locker project was a teaching moment, reminding us that we each carry a responsibility to ourselves, to our peers, and especially to our community. The profound business of making the world a better place is never-ending, and our task is never finished.”

A Blueprint Others Can Follow

When asked what advice she’d give to colleagues looking to make a similar impact, Dr. Davis returned to the ethical heart of the project: Don’t design “help” in a way that pressures students who are already carrying heavy loads to participate. “Always consider the position that your students are in and what we are asking them to do.”

She encouraged service structures that prioritize participation over financial contribution. “Consider aspects of service where the students can give their time instead of other ways of giving.”

Because this was much more than a donation drive. It was a learning opportunity that made visible to Carroll students (and to readers of this article) what support looks like, and what a community—or a class—can do when it decides, together, to respond.

“After all these years,” a teary-eyed Dr. Davis shared, “my students can still inspire and surprise me.”

Give to the Food Locker

You can also order directly from our Amazon Wish List via the button below and have needed items sent to the Food Locker.